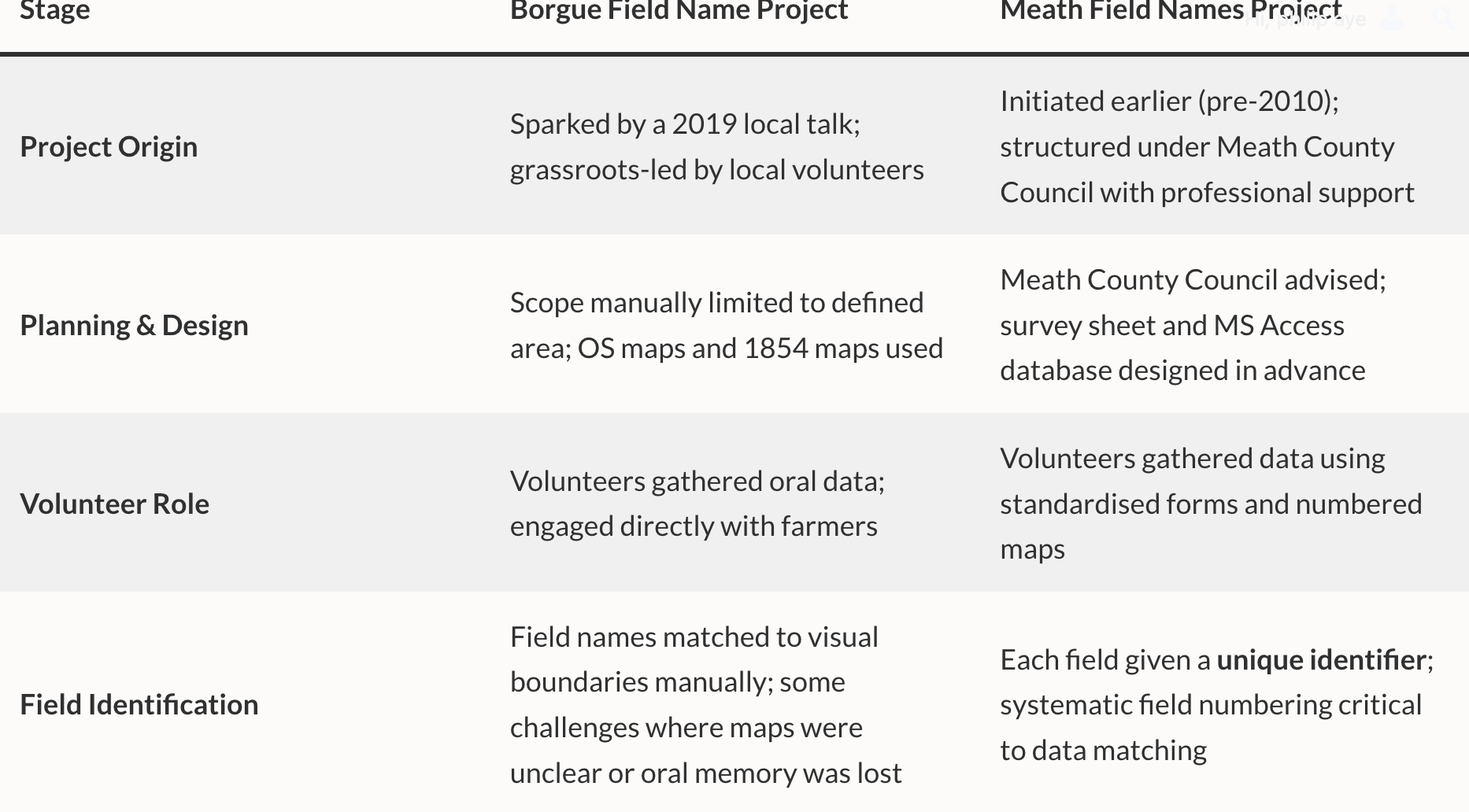

Here’s a comparative table of the Borgue Field Name Project and the Meath Field Names Project, showing the key steps and differences in methodology across planning, data collection, recording, and digitisation stages.

Both the Borgue and Meath field name projects share a common foundation in combining local knowledge with structured data collection and digital mapping, underpinned by modest funding, local authority expertise, and dedicated technical support. Each evolved through clearly defined phases—initial collection, database recording, and eventual digitisation—drawing on a mix of volunteer effort and professional or council staff input. Both projects were long-term endeavours rather than one-off surveys, with periods of intense activity followed by quieter consolidation phases. While Borgue used an artist’s map and exhibitions to engage the community during the project’s life, Meath produced a more formal legacy in the form of a published book, even before all data had been fully mapped. The key difference lies in emphasis: Borgue had a more fluid, oral-history-driven approach, while Meath’s was structurally rigorous from the outset, with unique field identifiers and a formal database schema.

| Stage | Borgue Field Name Project | Meath Field Names Project |

|---|---|---|

| Project Origin | Sparked by a 2019 local talk; grassroots-led by local volunteers | Initiated earlier (pre-2010); structured under Meath County Council with professional support |

| Planning & Design | Scope manually limited to defined area; OS maps and 1854 maps used | Meath County Council advised; survey sheet and MS Access database designed in advance |

| Volunteer Role | Volunteers gathered oral data; engaged directly with farmers | Volunteers gathered data using standardised forms and numbered maps |

| Field Identification | Field names matched to visual boundaries manually; some challenges where maps were unclear or oral memory was lost | Each field given a unique identifier; systematic field numbering critical to data matching |

| Recording System | Spreadsheet-based; compiled with map annotations; shared with analysts for linguistic input | Microsoft Access database built to enable structured entry, reduce errors, and allow queries |

| Start of Data Entry | Circa 2019–2020; done concurrently with collection | Began September 2010, continued to Sept 2012 |

| Supplementary Sources | Historical estate maps (1780s–1800s), OS 1908 field numbers, farm diaries, oral history | Checked official datasets (OSI, PRA, Dept. of Agriculture) – found none suitable |

| Digitisation Approach | Manual overlay of names on modern maps; painted and digital maps created | Intended from start; used MapInfo to align with council GIS; digitisation began 2011 |

| Digitisation Team | Initially local effort; then refined by community collaborators | Started with GIS students; completed via professional contract (Mallon Technology, 2012) |

| GIS Output | Interactive digital map of field names; still in progress | Fully clickable digital map per townland; integrated with other datasets like field monuments |

| Challenges | Loss of local memory; reluctance to share; oral variation; data loss if informant passed | Map loss = data unlinking; digitisation too large for volunteers; dataset access from agencies limited |

| Community Outputs & Engagement | Painted artist’s map created during project; used for public exhibition panels; strong engagement tool | Later published a comprehensive book compiling the survey findings; despite project being incomplete |